The Fastest Man You Never Knew

Episode 3: The Race Begins with Marshall “Major” Taylor

Before the wheels cut the wind, before the cheers rise from velodromes across continents, we invite you into the disciplined cadence of a life propelled by defiance and grace. What follows is not a highlight reel, but a restoration — fragments of press clippings, photographs, and testimonies that together reveal Marshall “Major” Taylor, the first African American world champion in cycling.

As you scroll, you’ll encounter images of his victories, accounts of his battles against segregation, and echoes of his relentless pursuit of excellence — each artifact a portal into Taylor’s vision, endurance, and the cultural resistance of turn‑of‑the‑century Black achievement.

This is the full reveal. Not just of a cyclist, but of a movement toward speed, dignity, and the unyielding demand to be seen.

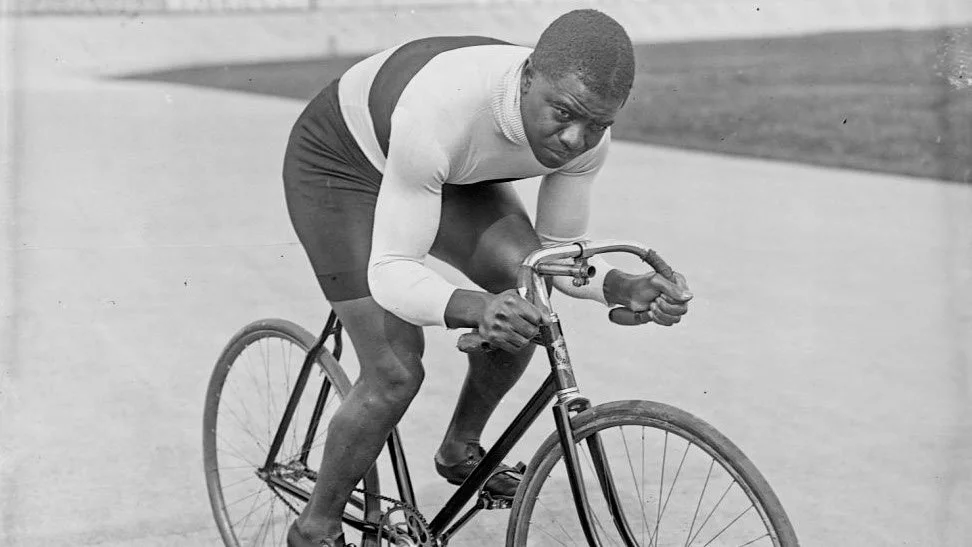

Marshall “Major” Taylor, the Black Cyclone Captured here in dual motion and stillness, Marshall Walter Taylor (1878–1932) defied gravity and segregation to become the first African American world champion in cycling. Known as the “Black Cyclone,” Taylor set multiple world records between 1898 and 1899, including the one-mile sprint title at the 1899 World Track Championships in Montreal.

His victories were not just athletic — they were acts of resistance. Taylor faced bans from racing venues, physical attacks on the track, and relentless racism from competitors and spectators alike. Yet he raced across the U.S., Europe, and Australia, beating the world’s best and refusing to be erased.

This image, showing Taylor in both poised portrait and aerodynamic action, reflects the duality of his legacy: a man of quiet dignity and explosive speed, whose story continues to inspire generations of athletes and advocates.

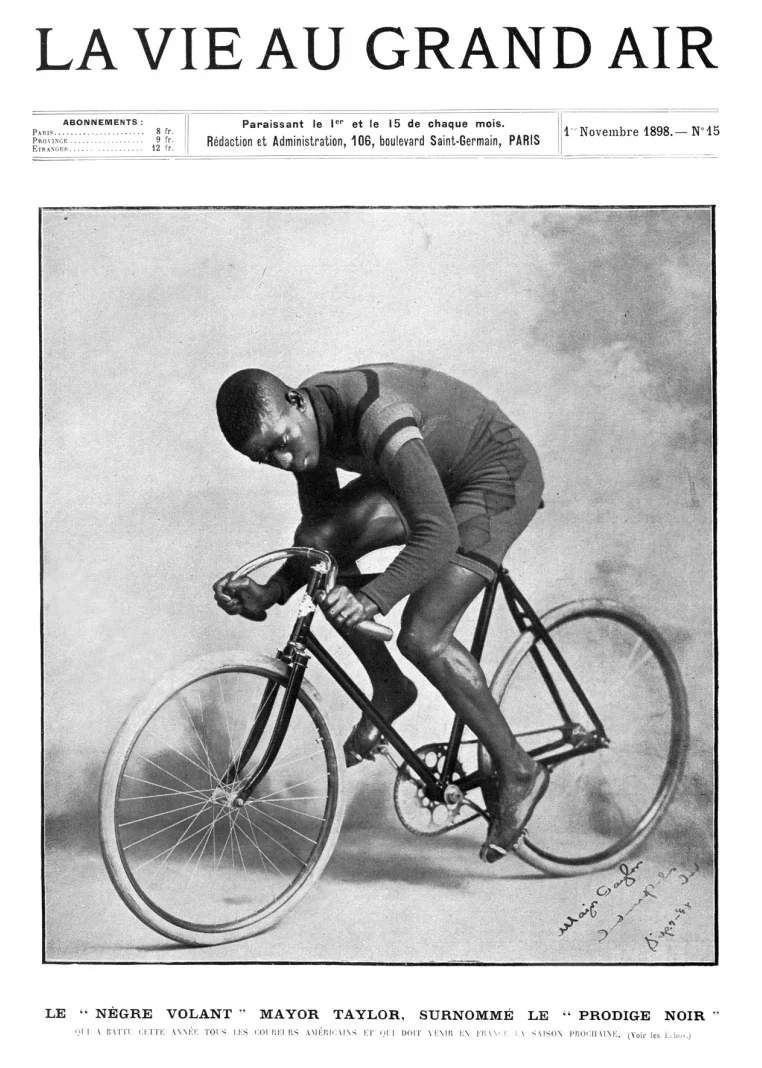

Major Taylor on the Cover of La Vie au Grand Air, November 1898 This French sports magazine captured Marshall “Major” Taylor at the height of his early fame, naming him le nègre volant (“the flying negro”) and le prodige noir (“the Black prodigy”). At just 20 years old, Taylor had already defeated every top American cyclist and was preparing to race in Europe, where he would go on to break records and challenge racial barriers abroad.

The caption beneath his image reads: “Who beat all American riders this year and is expected to come to France next season.” His signature, printed on the photo, declares him 1er sprinter du monde — the world’s top sprinter.

This cover marks a rare moment of international recognition for a Black athlete in the 19th century, and foreshadows Taylor’s global impact as the first African American world champion in cycling.

Major Taylor in Motion, circa 1900 Marshall “Major” Taylor was known for his explosive sprinting style and aerodynamic form, captured here in the low, forward-leaning posture that helped him dominate the track. By the turn of the 20th century, Taylor had become the first African American to win a world championship in cycling, claiming the one-mile sprint title in 1899.

He competed internationally at a time when racial segregation barred him from many U.S. races. In Europe and Australia, he found both acclaim and continued resistance, often racing under threat of sabotage or violence. Despite these barriers, Taylor set seven world records and became one of the most celebrated athletes of his era.

This image reflects not only his physical precision but the quiet intensity with which he challenged the limits imposed on him — a symbol of speed, strategy, and unyielding dignity.

Major Taylor in Competition, Early 1900s This photograph captures Marshall “Major” Taylor in full stride, racing ahead of a competitor before a crowd of spectators — a familiar scene during his peak years as one of the fastest cyclists in the world. By 1900, Taylor had set multiple world records and claimed the one-mile sprint title at the 1899 World Championships in Montreal, becoming the first African American to win a world title in cycling.

Major Taylor at the Starting Line, Early 1900s This photograph captures the tense ritual before a race — Taylor held steady by an official, flanked by a white competitor, and watched by suited men and a grandstand of spectators. These moments were often fraught with more than athletic anticipation: Taylor faced open hostility, sabotage, and exclusion throughout his career, especially in the United States.

Major Taylor Leading the Pack, Early 1900s This photograph captures Marshall “Major” Taylor in full flight, racing on a banked wooden velodrome — the signature surface of elite track cycling in the early 20th century.

By 1899, Taylor had claimed the one-mile sprint title at the World Championships in Montreal, becoming the first African American to win a cycling world title.

This image, with Taylor surging ahead of his competitor, is more than a snapshot of athleticism — it’s a testament to his resilience, speed, and the quiet revolution of a Black man refusing to be held back.

Major Taylor in Later Years, circa 1920s This photograph shows Marshall “Major” Taylor dressed in a double-breasted overcoat and hat, reflecting the quiet dignity with which he carried himself after retiring from professional cycling. Though he had once been one of the highest-paid athletes in the world, Taylor’s post-racing years were marked by financial hardship and obscurity.

After retiring in 1910, he published his autobiography The Fastest Bicycle Rider in the World in 1928, hoping to reclaim his legacy and inspire future generations. He spent his final years in Chicago, living in modest conditions and largely forgotten by the sporting world.

Taylor died in 1932 and was buried in an unmarked grave until a group of cyclists and the Schwinn Bicycle Company funded a proper headstone in 1948. This image stands as a quiet testament to a man who once outraced the world — and whose legacy continues to gain speed.

This image shows the bronze relief sculpture from the Major Taylor monument in Worcester, Massachusetts, dedicated in 2008.

Key Facts About the Monument

Location: Outside the Worcester Public Library in Salem Square — the first monument in the city honoring an individual African American.

Sculptor: Created by Antonio Tobias Mendez, a Maryland artist known for public memorials including the Thurgood Marshall Memorial and the U.S. Navy Memorial.

Historical Context:

Taylor was the 1899 world champion in the one-mile sprint — the first African American to win a cycling world title.

He held seven world records by the end of 1898 and competed internationally despite facing racial exclusion in the U.S..

The velodrome depicted in the sculpture is based on a photograph of Taylor racing at the Sydney Cricket Ground in Australia, where he was a major draw.

Legacy Impact:

The monument was commissioned by the Major Taylor Association, with support from athletes like Edwin Moses and Greg LeMond, who spoke at the dedication.

It has become a gathering place for cycling events and a symbol of Worcester’s role in sports history.