A Mirror to Madness

Episode 6: Madness in the Mirror: The Nellie Bly Reckoning

Before the door clicks shut, before the silence of confinement swallows its first breath, we invite you into the resonance of a legacy nearly obscured. What follows is not a confession, but a reclamation — a constellation of surviving fragments that together reveal Elizabeth Cochran, known to history as Nellie Bly, the journalist whose daring descent into the asylum exposed truths the world tried to ignore.

As you scroll, you’ll encounter portraits, and where Bly’s vision pierced the darkness — each artifact a portal into her courage, resilience, and the cultural defiance of a 19th‑century woman navigating walls meant to erase her.

This is the full reveal. Not just of a name, but of a movement.

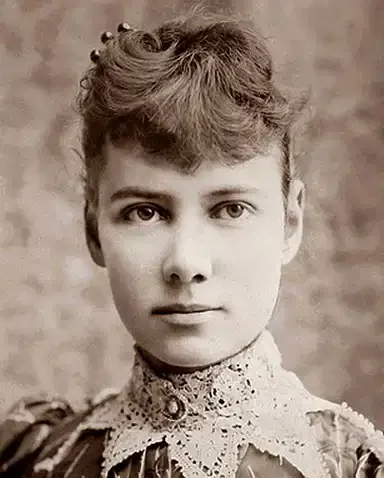

This sepia-toned portrait introduces Elizabeth Jane Cochran — later known to the world as Nellie Bly — at the threshold of her transformation into a pioneering journalist.

Born May 5, 1864, in Cochran’s Mills, Pennsylvania, Elizabeth Cochran was nicknamed “Pink” as a child for her bright dresses — a contrast to the drab tones of her era.

This portrait likely dates to her early twenties, around the time she began writing for the Pittsburgh Dispatch under the pseudonym “Lonely Orphan Girl” — a name that reflected both her personal loss and her social critique.

The image reflects a moment before her most famous acts — before she feigned insanity to expose conditions at Blackwell’s Island Asylum, and before she circled the globe in 72 days to rival Jules Verne’s fictional Phileas Fogg.

Elizabeth Cochran (Nellie Bly) – Key Facts

Birth and Early Life: Elizabeth Jane Cochran was born on May 5, 1864, in Cochran’s Mills, Pennsylvania. She later adopted the pen name Nellie Bly when she began writing for the Pittsburgh Dispatch.

Career Beginnings: Her first article, The Girl Puzzle (1885), argued for expanded opportunities for women and challenged traditional gender roles. This piece led to her hiring as a reporter.

Investigative Work: In 1887, Bly feigned insanity to gain admission to Blackwell’s Island Asylum in New York. Her exposé, Ten Days in a Mad-House, revealed abusive conditions and led to reforms in mental health care.

Around the World Journey: In 1889–1890, Bly traveled around the world in 72 days, inspired by Jules Verne’s Around the World in Eighty Days. Her journey was widely publicized and made her internationally famous.

Later Life: Bly continued to write and later worked as an industrialist and inventor. She died on January 27, 1922, in New York City.

This photograph of Elizabeth Cochran, known publicly as Nellie Bly, was taken later in her life and reflects her evolution beyond journalism into industrial leadership and advocacy. By the early 20th century, Bly had transitioned from undercover reporting to roles that expanded her influence in business and humanitarian work.

After marrying industrialist Robert Seaman in 1895, Bly became president of the Iron Clad Manufacturing Company, where she oversaw operations and patented several inventions, including a novel oil drum and stacking garbage can. Her leadership in a male-dominated industry was rare for the time and marked a significant shift in her public identity—from reporter to executive.

During World War I, Bly returned to journalism, reporting from the Eastern Front for the New York Evening Journal. She interviewed wounded soldiers, covered relief efforts, and advocated for better conditions for refugees and women affected by the war. Her writing during this period focused less on exposé and more on empathy, resilience, and global awareness.

This image, with its textured hat and composed expression, captures Bly as a seasoned public figure. No longer the young woman infiltrating institutions, she had become a symbol of persistence and reinvention—someone who used her platform to challenge norms across multiple domains. It stands as a visual testament to her later accomplishments and enduring legacy.

This final image marks the closing chapter of Elizabeth Cochran’s life and legacy. Buried under her married name, Elizabeth Cochrane Seaman, the gravestone honors her more widely known identity: Nellie Bly. She died on January 27, 1922, in New York City, after a career that spanned journalism, industrial leadership, and wartime reporting.

The headstone was dedicated decades later, on June 22, 1978, by the New York Press Club — a posthumous recognition of her impact on investigative journalism and women’s roles in the press. Though she was once buried in relative obscurity, this memorial ensures that her name, and the movement she helped shape, remain visible.

This image closes the page not with silence, but with acknowledgment — a final gesture of remembrance for a woman who refused to be forgotten.